Scheduling in an OS

Scheduling

OS has a bunch of scheduling policies that dictate how the processes should be scheduled. The processes running on the OS are called a workload. Each process is also called a job.

We also need a scheduling metric, in this case a turnaround time. More formally, \(T_{turnaround} = T_{completion} - T_{arrival}\)

Turnaround is a metric of performance, and similarly, there is another metric that is fairness.

First In, First Out

The most basic algorithm is First In, First Out or First Come, First Serve. Doesn't work as some processes may take a long amount of time and starve the other processes.

Shortest Job First

This is again a very dumb method to schedule things. It will take all the shortest jobs and execute them first, but in the process it'll starve a lot of processes that are longer in time. Also, if a long running process arrived first, it'll still complete that before the shorter jobs that arrive later.

Shortest Time to Completion First

This is done so that if a smaller job in SJF comes up it'll be given priority by context switching to that one. Once again, this will starve the larger process.

Response time as a metric

We define response time as \(T_{response} = T_{firstrun} - T_{arrival}\) This basically indicates how long it took for the first process to get scheduled for the first time.

Round Robin

This is more optimal as it gives a certain amount of time to each process without making it go to completion or wait for a long time.

For round robin, the length of the time slice is critical. It should be small for having better response times but not small enough that frequent context switching becomes an overhead.

Incorporating IO

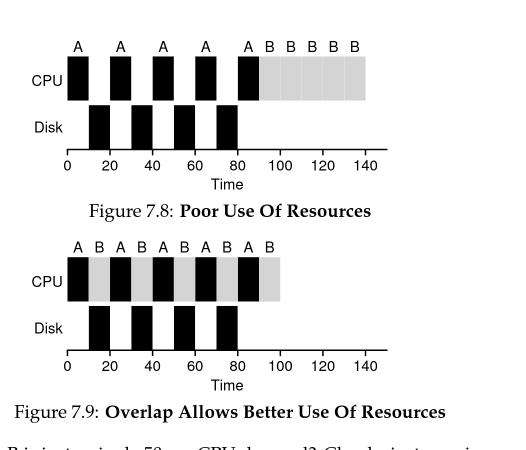

If there are 2 resources that have to be utilized, then when we are scheduling A, we'll also schedule B in the gaps of scheduling A.

Multi Level Feedback Queue

It tries to optimize two things,

- turnaround time

- response time

It has multiple distinct queues each assigned a different priority level. At any point:

- If Priority(A) > Priority(B), A runs and B doesn't

- If Priority(A) = Priority(B), A and B run in round robin.

MLFQ varies the priority of the processes based on the observed behaviour of the process.

How priority adjustment is done:

- When a job enters a system, it is placed at the highest priority (the topmost queue).

- If a job uses up its allotted time, then its priority reduces.

- If a job gives up the CPU before allotment is up, for example by using IO, then it stays at the same priority level.

However, this might lead to starvation of processes that don't have interactivity and have longer CPU domains. This can also lead to situations where one process hogs the CPU time by just executing 99% of the allotted time and then opening a file I/O. Finally, a long running batch program might also turn into an interactive program. To counter this, we interoduce a new rule.

- After some time period \(S\), move all jobs to the topmost queue.

Proportional Share

This is also called fair-share scheduling. An early example of this is called as the lottery scheduling.

The main idea is to use tickets. For a process A that needs 75% of the CPU time it should have 75% of the tickets. Now we randomly generate ticket numbers and use the corresponding process mapped to it. In the long run, it will fall to 75% of the CPU time.

The implementation is very simple. Have a list of processes along with the allotted number of tickets. You then generate a random number from in between 0 and the total number of tickets. After that, you iterate through the list and then stop at the process where the sum of the tickets so far are more than the number you generated.

Stride Scheduling

Over short time scales, randomness does not allow for fair share. For this, we have stride scheduling which is a deterministic fair-share scheduler.

Each job in the system has a stride which is inverse to the number of tickets it has. We create a pass value for each process. Each time, we choose the one with the least pass value and add its stride to the pass value.

Completely fair share (Linux Scheduler)

It has a counter called as a virtual runtime (vruntime). As each process runs, it accumulates

more of this. When a scheduling decision occurs, CFS will pick the one with the least

vruntime.

There are various parameters on how to schedule things. The first one is sched_latency. This

is usually 48ms, divided by the number of processes the OS has. If there are too many

processes running, then there would be too many context switches and it'd be massively painful

For this, there is another parameter called min_granularity. This is usually set to 6ms. CFS

is operated upon by a timer interrupt. If the job slice is not a perfect multiple of the timer

it is still not a problem as CFS tracks vruntime precisely and in the long run will

approximate the ideal CPU sharing.

CFS also enables control over process priority by using a property of the process called niceness. Each niceness has a weight associated with it that allows it to compute the effective time slice that the process should use.

The time slice is scaled to the weight of the process by the sum of weights of the other

processes times the sched_latency. Similarly, runtime is also scaled down by the weight of

the process.

\[ time\_slice_k = \frac{weight_k}{\sum_{i=0}^{n - 1}weight_i}\cdot sched\_latency \]

\[ vruntime_i = vruntime_i + \frac{weight_0}{weight_i}\cdot runtime_i \]

The way these weights were created, it allows the scheduler to run two different sets of two processes in the exact same manner if difference in the niceness between the two processes is the same in each set.

CFS keeps active processes in a red black tree to fetch the next one as fast as possible. This allows it to search for the a process in \(\mathcal{O}(\log n)\). Insertion and deletion also follow similar time complexities. This is noticeably more efficient than linear.

A singular problem I know of is starvation in case of sleeping and I/O bound processes. To prevent sleeping and IO bound processes from hoarding the CPU time, they are set to the minimum vruntime of the RB-tree. This, however, makes short and frequently sleeping processes starve massively.